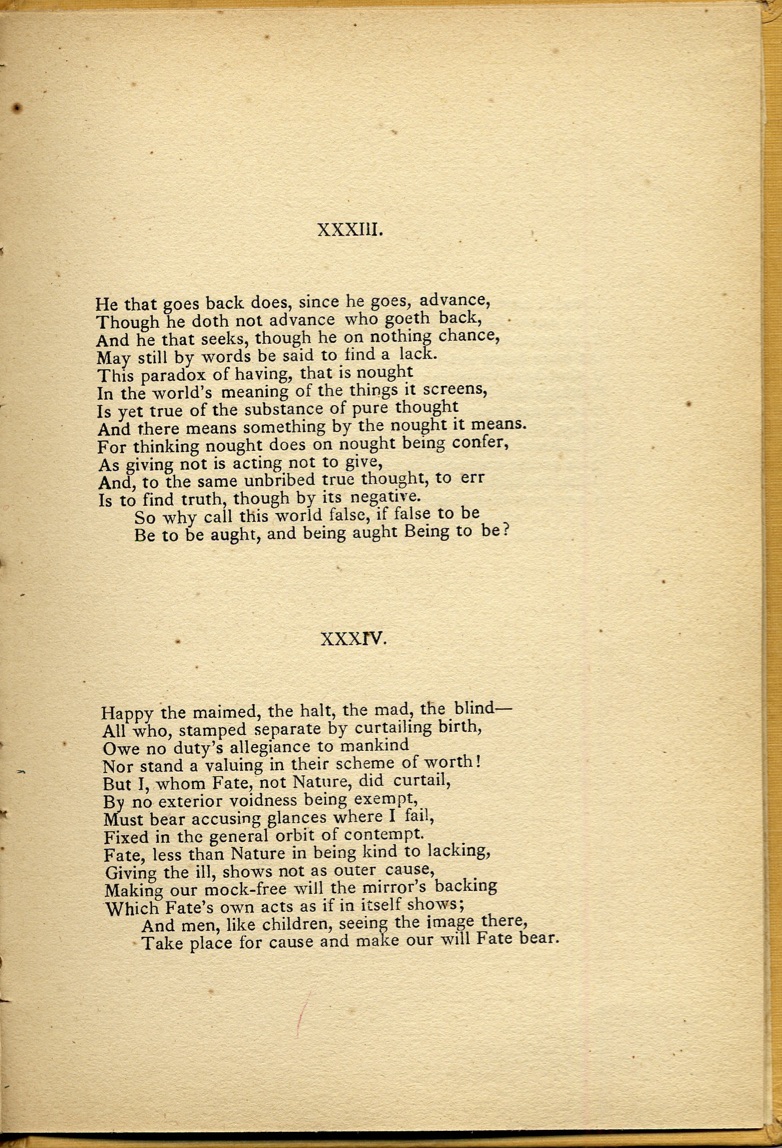

Fernando Pessoa's "35 Sonnets" (1918)

One of two works self-published in 1918, Pessoa wrote these sonnets in English very much under the influence of Shakespeare (and Hopkins, by the looks of it). He sent his collection to several British journals to be reviewed, where one critic in the Times Literary Supplement noted that Pessoa's "command of English is less remarkable than his knowledge of Elizabethan English." As I first encountered a PDF of the book in 2012, I was left a little bewildered. How was this, and Pessoa's other verso inglês, not more widely known and read? These poems are right up there with his major work - and even within an oeuvre defined by its strangeness, its otherness, these poems are doing something really quite weird.

It's also the admittedly amateurish or "outsider" quality of some of the poems that renders those sharp turns of phrase all the more cutting, as what's profound becomes uncanny. Much like when I read the Book of Disquiet, I can never not imagine my reading as if I were picking loose leaf pages at random out of a discarded steamer trunk, the paper as sallow as those of the book scanned here below - reading words that, even though they are passing through my mind as I read them, and even though I and many others are aware of Fernando Pessoa and Alberto Caeiro and Alvero de Campos and his other personas, that the oblivion these words issue from outweighs my awareness, that pushes back and struggles against my reading as a kind of magnetic pull towards wanting to be forgotten. I mean, I can admit it - I often forget about Pessoa and his work, he slips my mind. I rediscover him on my book shelf. Here is the oblivion that everything which is past is part of, that it all becomes, to put the body in nobody - that we will never know how these words came to us, they just are. Closed between the covers of a book, or suspended in code that is only rendered as text whenever our browsing calls it into being. Or they are found, these words and works, a bizarre and random instantiation of what was only previously imaginable - not imagined, but what was possible to have been imagined. One can easily invoke the legend of Kafka here, too, though what's so uniquely troubling with Pessoa is how we get the inner life of a man who not only has disappeared, but who never was in the first place. There's a certain sensation that emanates from Pessoa's writing, an aversion at its subtlest and a horror at its most acute, which is felt in relation to the givenness of what others always seem to point to as the "facts of life" - the things and ways of the world, the world as a world itself, and our being in it, a part of it. That things are real, that they are - an absurdity, the knowledge of which goads from the page and infects and corrodes the knower. Not to go too much further on this silly tangent, but reading Pessoa reminds me of how literally everything that's everything is made up - which does not mean the same as make believe. For what point do we inhabit, from which we can believe? It is as though I often graze some infinitely unsettling realization that I just barely, luckily, avoid having. This is particularly the case with the Book of Disquiet, but I get the same vague sense of vertigo reading these sonnets - which in their own way enhance this uneasiness precisely because they themselves, the poems, are so rarely read.

At any rate, to me this slender chapbook is a kind of conservatory greenhouse full of overgrown ferns, orchids and corpse flowers stuck somewhere on a run-down East Midlands country estate. Pessoa practices upon English what was so often exacted upon the spoils of British colonialism: he exoticizes it. Moreover, the effect these sonnets achieve is one of rendering English - or, more narrowly, the idiom of the Elizabethan sonnet - foreign to (and yet more strangely) itself.